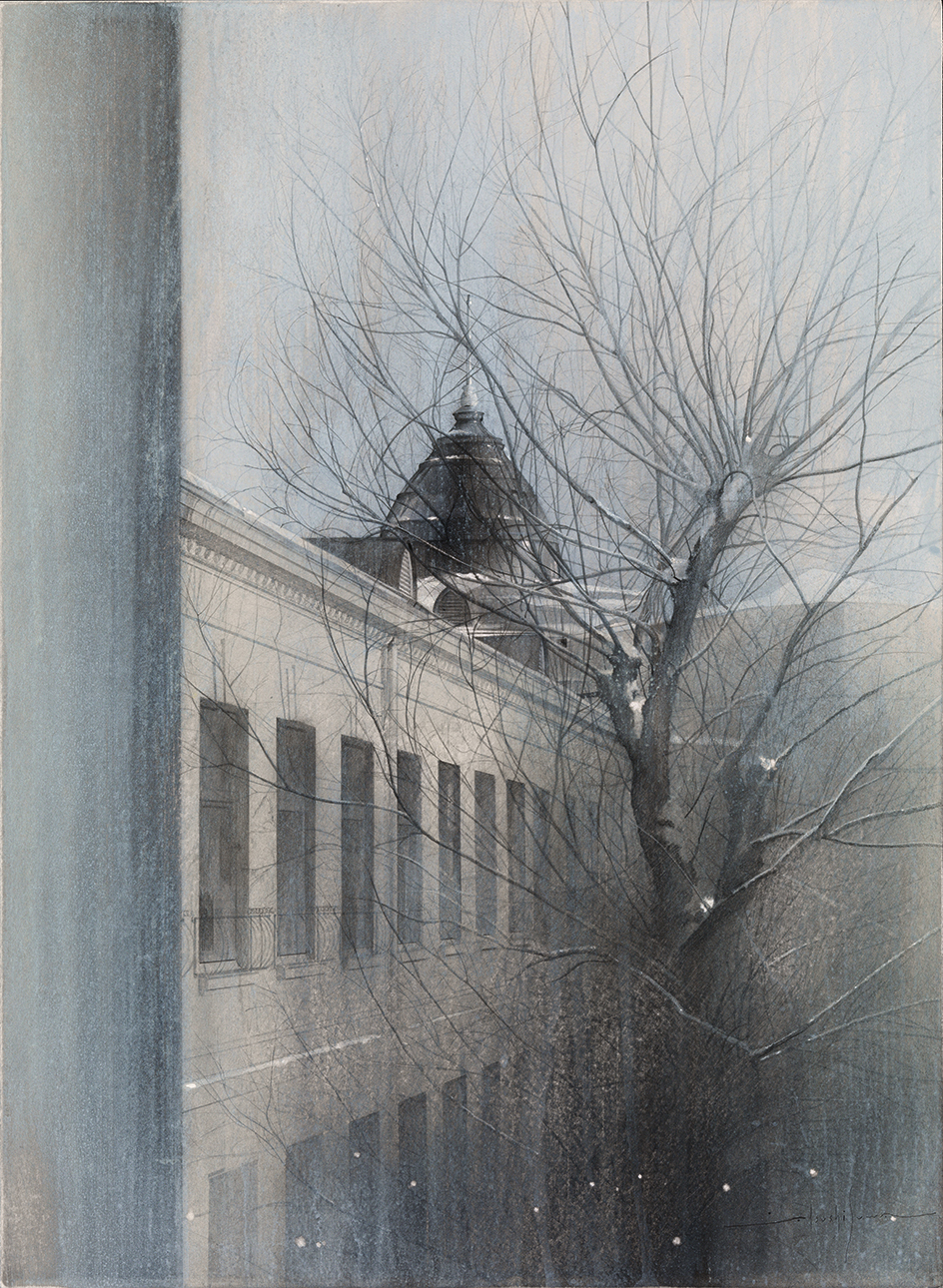

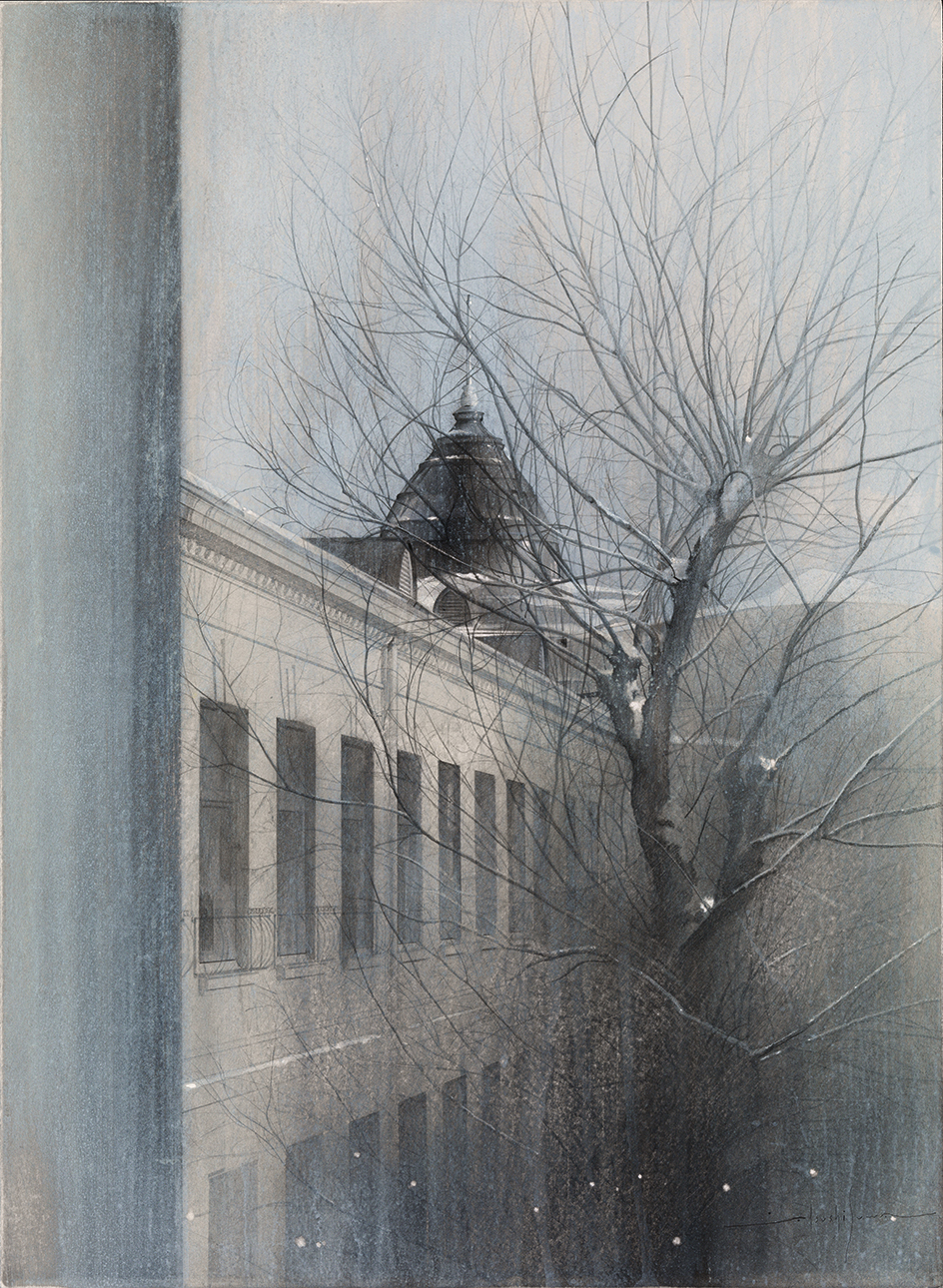

The Japanese Planted a Tree

2016

45.5 × 33.3 cm

Acrylic and pencil on panel/ kentboard

Private collection

想像力は、世の中で気安く言われる程、無限でも豊かなものでもなく、貧弱で限界がある。画家はむかしから外部にモチーフや衝動を求めてきた。私は見ようとする行為そのものの意味自体を、掘り下げようと試みる。「見尽くした」と認識の省略が常態化し、そこかしこに置き忘れてしまった、心理的盲点を残さず回収するために。実見の機会はかけがえのないもので、絶対的である。しかし描こうとする対象者が目の前にいない……例えば既に死亡していて対峙することが不可能な場合、私はどんな画家にとっても最も基本的な「見る」という行為を再検討し、その拡張を試みなければならなくなる。そうして、濁った混沌から時間を経て、やっと浮かび上がってきた上澄みを注意深く掬いとるように、絵画として表象化する。

その例のひとつが《HARBIN 1945 WINTER》である。父とその家族は、日本の敗戦直前、多くの満蒙開拓団と民間人がそうであったように、関東軍に生きたカカシとして置き去りにされ、日ソ中立条約を破棄したソ連軍の侵攻に晒された。いわばジェノサイドの渦中、満州難民として中国東北部を逃亡し、たどり着いた哈爾濱の日本人難民収容所で、祖母と叔父は伝染病と飢餓に苦しんで死んだ。この絵は、凍った大地に埋葬された祖母の姿を70年後に描こうとしたものであるが、私は戦後生まれなので、当然彼女の姿を見たことはない。生き残った者は引き揚げの際に携帯物を制限されていたから、祖母の姿を映した写真も渡航前の僅かなものしか残っていなかった。私は実際に生還した父の手記を頼りに、彼らが辿った道行きをなぞる旅に出た。そこで思い知ったのは、70年の隔たりだった。

絵画において徹底的に拡張された「見る」という行為は、こう着状態と突破を繰り返し、対象との関係を無制限に更新する、絵画に取組んでいる限り、誰も立ち去ることはなく、死者は召喚され、時間は引き延ばされてゆく。「見る」は、その行為を完了しえず、どこかに必ず存在するはずの真実の前で試行錯誤を繰り返す。その永続運動を可能にするから、描くことは美しく、不可能性を扱えるが故に絵画は最強のメディア足り得る。しかしながら、その様は、滑稽で悲しいものだ。

.jpg)

HARBIN 1945 WINTER

2015-16

587 × 840 mm

Pencil on graph paper

Private Collection

ETV特集「忘れられた人々の肖像〜画家・諏訪敦 “満州難民”を描く〜」2016年

Contrary to popular belief, imagination is neither infinite nor rich, but rather limited and meager. Painters have always pursued motifs and inspiration from the outside world, but I intend to investigate the act of “seeing” itself, and dig deeper into the true definition of perception. To completely patch blind spots and loopholes buried under layers of misconception, to ask myself once again, have I really seen it all? To see something in person is divine. But when the subject is not present…for example, if the subject is deceased, I must reconsider the idea of “seeing” and "see" beyond time. As if the image would gradually surface from the depth of a murky chaos, I carefully transform the fragile outcome into a painting.

One example is “HARBIN 1945 ,WINTER”. Like the other Japanese left stranded in Manchuria after the war by the Japanese Army, my father and his family were taken by the invasion of the Soviet Union who broke the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact. Amidst the genocide, they managed their way through Northern China and eventually landed in a Japanese refugee camp in Harbin, where they fell victim to sickness and starvation. This is a painting of my grandmother, attempted 70 years after her burial into the frozen landscape. Since the survivors were only allowed a limited number of processions upon returning to Japan, I have only seen a few photographs of her taken before her passage to Manchuria that my father kept. I set out to retrace their journey, relying on the diary my father kept. What I discovered was an ocean of 70 years.

The act of seeing, portrayed as a painting, is a spiral between the artist and the subject, the deadlock and the breakthrough, where no one leaves and the dead are resurrected ,where time itself is expanded. “Seeing” never completes its task, treading water in front of a “reality” that exists somewhere. This is what makes painting so beautiful, the endless cycle, and ,the potential to realize the impossible. But then again, it is indeed rather sad and comical.

HARBIN 1945 WINTER

2015-16

1455 x 2273 × 30 mm

Oil on canvas/panel

Collection : Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art (Hiroshima Japan)

Yorishiro

2016-17

861 x 1958 × 33 mm

Mixed media

Private Collection